The Concept of “Square and Round” in Vietnamese Culture

In Vietnamese, there is a saying that may sound a bit illogical or amusing at first: “The mother is round, the child is square.”

The phrase implies “a smooth and successful childbirth, where both mother and baby are healthy and the child is born without any defects — just as everyone hopes for.”

However, if this saying were translated literally into another language, especially Western ones, it would be very difficult to convey its auspicious meaning to the listener. The simple reason is that Western cultures do not share the same philosophical and cultural concepts as we do.

In Western thought, “square” and “round” do not suggest harmony or completeness — in fact, they are often seen as opposites. From a geometrical point of view, these are two entirely different shapes. When placed side by side, they evoke contrast; when placed within each other, they do not fit.

In contrast, within Vietnamese culture, these two shapes — the square and the circle — often go hand in hand. When combined, they symbolize a harmonious union in accordance with the natural order of the universe, resulting in something auspicious and blessed.

Why is that? Naturally, this seeming paradox carries a positive meaning that can be explained. It originates from deeply rooted folk concepts that have long been accepted as symbols of balance and goodness. When these “virtuous elements” are combined, they give rise to benevolent outcomes.

Indeed, Vietnamese cultural life has been profoundly influenced by three great philosophical and religious traditions — Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism. The influence of these “Three Teachings” (Tam giáo) permeates daily customs, language, and even the collective consciousness of the Vietnamese people. It runs in our veins, shaping our way of thinking for millennia.

Among these influences, the Buddhist law of cause and effect has become a foundational principle for many folk beliefs. Thus, from causes that are inherently good arise favorable and wholesome results — just as the saying goes, “Like tree, like fruit,” or “Like father, like son.”

So, on what foundation does the concept of “square and round” (vuông tròn) stand to become one of the “fundamental virtues” in Vietnamese philosophy and culture?

To answer this, we need not search far. Let us begin with the folk stories that vividly reflect the essence of Vietnamese cultural life — for within them lie the origins of these symbolic concepts. The first and most obvious evidence can be found in the legend of Bánh Chưng and Bánh Dày.

This story, well known to most Vietnamese, originates from the era of the Hùng Kings — the earliest royal dynasty of the Vietnamese people. It tells of a king who, wishing to choose a successor among his sons, held a contest. Each prince was asked to offer a dish representing the highest expression of filial piety and devotion.

One of the younger princes, coming from a modest background and unable to afford rare or luxurious ingredients, created two simple cakes from everyday rice — Bánh Chưng and Bánh Dày — as his offerings to his parents. The king, deeply moved by the simplicity and profound symbolism of these gifts, praised them greatly and chose that prince as his heir.

To be accepted, the young prince must have explained his creations with meanings noble enough to move his father. And indeed, he did. Everyone knows that Bánh Chưng is square while Bánh Dày is round — the former symbolizing the Earth, the latter symbolizing the Sky.

In ancient cosmology, shared not only in Vietnam but across many early civilizations, people believed that the Earth was a flat, square plane, while the Sky was a vast, round dome covering it — much like an inverted bowl over a tray. Within this space between Heaven and Earth existed all living beings. People believed that if one kept walking or sailing in one direction, eventually one would reach “the edge of Heaven and the end of Earth” — and fall into the infinite void beyond.

Thus, Heaven (Trời) and Earth (Đất) formed the earliest dual concepts of the human worldview — the foundation upon which the philosophy of “vuông tròn” was born.

Moreover, Heaven and Earth are not only seen as the structure of the cosmos, but also as the origin of all life. Vietnamese expressions such as “Trời đất sinh ra ta” (“Heaven and Earth gave birth to me”) or the familiar invocation “Ông Trời” (“Grandfather Heaven”) personify these two natural entities while implying the sacred source of human existence.

In this worldview, Heaven is the Father, and Earth is the Mother. In moments of hardship or despair, people instinctively cry out, “Trời đất ơi!” (“Oh Heaven and Earth!”), and sometimes even “Trời đất cha mẹ ơi!” (“Oh Heaven, Earth, and parents!”) — a heartfelt call to the two primal forces that gave them life.

In the Eastern cosmology, the concept of “square and round” (vuông tròn) symbolizes the harmony between Heaven and Earth, or Càn and Khôn, or in philosophical terms, Yin and Yang.

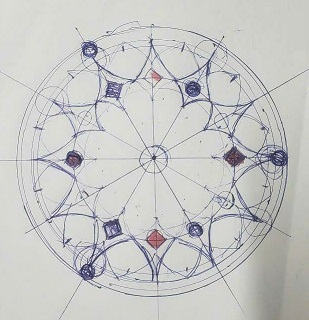

In traditional Eastern architecture, this harmony is always reflected in form and proportion. Alongside the essential straight lines (symbolizing the masculine, the firm, the active), one always finds curves and circular motifs (symbolizing the feminine, the gentle, the receptive). The result is a visual and spiritual balance between Yin and Yang. The curved rooflines, the circular windows — all are manifestations of this philosophy.

By contrast, in Western architecture, circular forms are far less common. Buildings tend to favor the straight, the angular, and the box-like — emphasizing logic and structure rather than harmony with natural flow.

Even in the Nguyễn Dynasty, this philosophy was subtly embedded in the design of the currency in circulation. The traditional cash coins (tiền kẽm) were round in shape with a square hole in the center, and on each of the four corners of the square were four Chinese characters. The square hole allowed coins to be strung together for convenience in carrying and trade.

Yet beyond mere practicality, the design embodied profound symbolic meaning: the round outer edge represented Heaven, and the square center symbolized Earth — a metaphor for the Emperor’s divine role as the Son of Heaven ruling over all under Heaven. The royal couple was revered as “cha mẹ dân” (“the parents of the people”), and the subjects were called “con dân” (“children of the realm”). The square and round form of the coin also carried a blessing — that the dynasty might endure eternally, like Heaven and Earth themselves.

In the eyes of an ordinary person, there is nothing more perfect or sacred than father and mother. Beyond the metaphor of parental figures, Heaven and Earth also embody the ideas of eternity, vastness, and boundless abundance.

Common expressions such as “A parent’s love is as vast as Heaven and the sea” (Công ơn cha mẹ như trời như biển) or “To live long with Heaven and Earth” (Sống lâu cùng trời đất) reflect this belief. In Vietnamese thought, Heaven and Earth are always paired, forming a harmonious concept that represents goodness, virtue, and perpetuity.

From this core idea of Heaven and Earth, it’s not hard to see how the notion of “square and round” (vuông tròn) emerged — as a way to bring that vast cosmic harmony down into daily life, making the abstract ideals of the universe feel closer, more human, and more tangible.

From the concept of square and round as symbols of Heaven and Earth, we move to another layer of meaning — the square and round of Yin and Yang, where their symbolism shifts: the round represents Yin (the feminine, receptive principle), and the square represents Yang (the masculine, active principle).

This distinction can be illustrated through various examples. However, in all cases, the harmonious balance between Yin and Yang is seen as a natural, auspicious union — one that always leads to good outcomes, to what is considered thiện (virtuous or wholesome).

Take, for instance, the Vietnamese proverb “Đầu tròn, gót vuông” (“A round head, square heels”). According to traditional Eastern medicine, the human body is divided into two halves: the upper half, ending with the head, embodies Yin (hence, the “round head”); the lower half, ending with the feet, embodies Yang (the “square heels”). When a physician examines a patient and finds the head cool (Yin) and the feet warm (Yang), it means the Yin-Yang balance is in harmony — nothing to worry about. Conversely, if this balance is reversed, illness may be present.

Traditional healers often advise: keep your head cool and your feet warm, and you will remain in good health — a living expression of the principle that harmony between Yin and Yang brings well-being.

Neither one of these shapes alone carries such meaning. A square by itself is merely a square; a circle alone is merely a circle. But when combined — square and round — they form the concept of Heaven and Earth, of harmonious Yin and Yang, embodying what is Thiện (goodness, virtue), harmony, and eternity.

Thus, when we say “Mẹ tròn con vuông” (“the mother is round, the child is square”), it is a way of expressing a happy, auspicious outcome — not a literal description. The mother, of course, is not actually round. During pregnancy her belly may be round, but after giving birth, it is no longer so. And the child certainly isn’t square. In reality, if a woman were to give birth to a baby that was literally square, it would be a tragedy — both mother and child would become the subject of shocking news overnight.

Try to imagine the situation of two childbirth announcements. If the doctor tells the father:

"Your wife has given birth. Mother is round, child is square. Congratulations!"

— it sounds perfectly normal and celebratory.

But if the phrasing were even slightly altered:

"We hereby inform you: your wife has given birth. The child is square."

— the father would probably be stunned, faint on the spot.

For example, in the saying:

"Do whatever you decide, as long as everything is square and round."

— it implies that as long as the outcome is good, harmonious, and without trouble or scandal, it’s acceptable.

Another example:

"A hundred years thinking of square and round,"

— here, “square and round” refers to the union of a couple, the harmony of yin and yang coming together to continue the cycle of life.

There is yin and yang, there is husband and wife,

Even heaven and earth revolve around the pair.

Or in folk verse:

"When the matter is dealt with square and round,

Even a thousand years of separation, still there is waiting."

— “square and round” (ngãi vuông tròn) symbolizes marital fidelity and enduring love.

This is about a lifelong union. Beyond the concept of “square and round” representing Heaven and Earth, or parents, or permanence, as mentioned earlier, the idea of square and round also symbolizes yin and yang, male and female, husband and wife. The difference is that, in the story of bánh chưng and bánh dày, if Heaven is symbolized as round and Earth as square, then in the understanding of the two sexes—male and female, yin and yang—square usually represents masculinity, while round represents femininity.

Women’s bodies are considered beautiful and feminine when they are rounded and curvaceous. Faces with too many sharp angles or square features are generally seen as less attractive and even harsh-looking. Such a body usually has more bones than flesh; if not bony, it might be too thin. A slim figure is acceptable, but it should be delicate. Certain areas, naturally designated as feminine features and often used to attract men, must be rounded. These curves—whether full breasts, buttocks, or other forms—are seen as part of the “circle.” In literature, they might be compared to Siamese coconuts, grapefruits, or balls. Sharp or angular forms are not considered feminine. Look at models: although many are very slim, their breasts and buttocks remain full and rounded. For ordinary women, those with less natural fullness may use tricks to enhance curves, and if necessary, cosmetic enhancements are sometimes used. These adjustments are simply ways to assert femininity, and there is no reason for criticism regarding women visiting cosmetic clinics.

Thúy Vân’s face in Đoạn Trường Tân Thanh is described as: “Full moon-like face, features well-rounded.” Though not the most strikingly beautiful, it exudes kindness and warmth. In physiognomy, kindness is considered a form of beauty in women. A round face may not be as aesthetically refined as an oval face, but it conveys benevolence. Women’s beauty comes in many forms: dazzling, delicate and sharp, or gentle and benevolent. The gentle beauty is thought to bring fortune to her husband and children. For a deeper understanding, one can refer to the writings of Vũ Tài Lục. A woman with harsh, rugged features is not only seen as less gentle and graceful but may also be considered inauspicious for her spouse and children.

Thus, even though Thúy Kiều is more strikingly beautiful than Thúy Vân, Vân is by no means lacking. In the lines: “Kiều càng sắc xảo mặn mà” versus Vân’s “So bề tài sắc lại là phần hơn,” Kiều is praised for her refined charm and sophisticated demeanor—what modern readers might call an elegant, graceful woman with “poised manner and pure spirit.” Yet, Thúy Vân’s beauty is hardly inferior. The poet affirms this balance: “Each has her own beauty; all are perfect in their own way.”

Conversely, square features on a man’s body are considered an advantage. A square, “block-shaped” face signifies masculinity. A man with a square jaw exudes authority and strength. While rugged or angular features may be seen as less desirable in women, in men they are attractive. Men do not need a soft, benevolent face; they need angularity—squared features from the face to the shoulders.

For women, round faces, necks, breasts, and hips convey femininity and appeal. In contrast, an attractive man should have a broad, muscular chest, but the chest should be squared, giving a strong, “cool” impression. A man with a rounded chest like a woman may appear unmanly. An overly developed chest in a man, resembling female traits, can indicate abnormal development or excess estrogen. Otherwise, it may signal laziness or lack of training. Broad, muscular shoulders are a clear sign of masculine strength and also suggest the ability to protect women if needed.

When describing women, writers often give them rounded, curvaceous features. But a man who is “round” often simply evokes the idea of being overweight or fat.

“There are those with just a bit of passion,

There are those beautifully round, yet he neglects the charming one.”

(Folk verse)

In general, East Asians, and the Japanese in particular, understand the appeal of curves. From architectural lines and decorations to the shapes of everyday objects, they often favor smooth, rounded forms. A Japanese car, besides having the advantages of reliable and durable machinery, attracts buyers—especially in Asia—because of its sleek, curvy design rather than sharp, angular lines.

In Vietnamese, a car is often called “cái xe,” with the word “cái” preceding it, which subtly conveys the idea of “thing” or object. Sometimes, a car is also referred to as “con xe,” similar to a piece in Chinese chess (“move the pawn, capture the rook,” etc.). But when a car is called “con,” it takes on a different nuance: a vehicle for battle. And speaking of battle evokes masculinity, the Yang aspect, and the male principle.

Before the country lost its sovereignty, the first cars assembled in Vietnam were the La Dalat model. It can be said that the designer’s sense of aesthetics was lacking. The original company, Citroën, supplied the machinery, while the car body was manufactured in Vietnam. Looking at the La Dalat, it was not very appealing—the bulky, awkward shape, with many sharp angles and few curves, gave it a distinctly rigid, square-edged appearance.

From another perspective, roundness also conveys the idea of completeness and wholeness.

"As a father’s labor is like Mount Tai,

A mother’s love like water flowing from its source,

With a single heart, serve mother and honor father,

Only by fulfilling filial duty completely can one be a true child."

Here, "round" signifies fulfillment and entirety. To “make it round” in one’s duties is both a figurative expression and a way of conveying the sense of completeness.

The author, having once served as a soldier, would like to share some practical observations about angular, squared-off forms, which often symbolize the strong, resolute character of men. Those who graduated from military academies such as the Da Lat Military Academy, Nha Trang Naval Officer School, Thu Duc Officer School, and the like, are well aware.

In the early stage, called the “Initiation Period” or “New Cadet Phase,” these academies applied a lifestyle practice known as “perpendicular living” to train young civilians into soldiers with pronounced masculinity. During this period, beyond physical training, leadership and command skills, and military ethics, cadets were trained to adopt a “right-angled” way of life. They had to walk at right angles, sit at right angles, and even lift a bowl to their mouth in a perpendicular motion. Every arrangement in the cadet’s room—from bedding to uniforms, books, and personal items—followed strict perpendicular alignment.

The purpose of this training was to gradually, step by step, transform the delicate, effeminate style of a civilian into the true physique and demeanor of a man. It was designed to create angular, squared-off lines not only on the body but also within the soul of the future officer. Rounded, fleshy parts of the body were gradually reduced, replaced by sharper, more defined contours. Arms, legs, chest, and shoulders all became squared; the jawline broadened (as a result of the “jaw meeting” exercise), and hair was cut in a “brush” style, forming a relatively square, chiseled face.

These angular features endowed young men with a sturdy, bold, decisive, and highly masculine appearance. Such “right-angled” physiques exerted a strong attraction toward the soft, curvaceous figures of women—opposite forces of yin and yang naturally drawing each other.

As the saying goes:

“Smart men seek wives in bustling markets,

Smart women seek husbands among soldiers.”

In summary, without understanding—or having a comprehensive perspective on—Eastern philosophy, it is difficult to fully appreciate the concept of “vuông tròn” (square and round) in Vietnamese language and culture.

Starting from the basic concept of Heaven and Earth, moving to the principle of Yin and Yang interacting and complementing each other, it ultimately leads to a notion of natural order. From this understanding, the concept of square and round can embody a harmonious and positive combination—what is considered the first notion of “Goodness” (innate virtue).

(St)